The thing about machines versus technology is that machines are tools. With technology, I’m the tool. (Still, when you need to hook up your new t.v. to your cable, satellite dish, game system, surround sound, AppleTV, and photo album, I’m the one to call. Trust me, your old cables won’t work.)

Blog in Progress

I spent the summer playing with machines. I took a letterpress class, in which I learned to typeset and use printing presses. I made little books and lots of stationery. It was SO fun. I got a knitting loom (good for afghans), and when that palled, I got a knitting machine (good for sweaters!).

VanderCook Printing Press in the SVA Print Shop

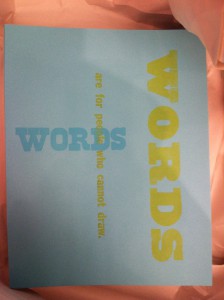

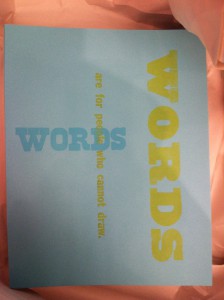

My letterpress stationery says, “Words are for people who cannot draw.” It’s meant to be ironic (stationery!), not insulting.

This knitting machine is completely manual. And fast!

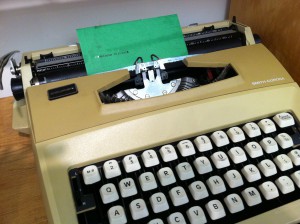

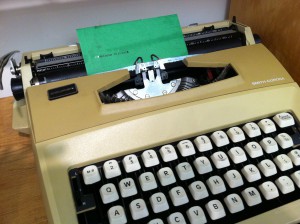

I played with a manual typewriter and am still considering using it to type my Master’s thesis next year. Why? Because it requires skill, and typewritten documents show the weight of the hands that typed them. Basically, they emboss the letters. I love all of my Apple products, but they can’t emboss. Why isn’t that in the commercials?

Manual typewriter from the 70s. Courier font. It does not get better than this.

If a love of machines can be genetic, I’m pretty sure it runs in my family of engineers, wannabe engineers, shouldabeen engineers (like me), and teachers. We all love tools. I have an electric drill of which I’m particularly fond (doubles as a screwdriver) and a glue gun that comes in handy a little more often than one would expect.

I love all kinds of paper cutters – from scissors and hand-held die cuts to rolling blade cutters, mat cutters, cleaver cutters, and guillotine cutters. I miss my power miter and table saws which still live in Connecticut because somehow they don’t quite fit into my apartment. But I brought my sewing machine, which makes buttonholes!

The guillotine paper cutter can take hundreds of sheets at once and won’t skew.

The first computer that my high school ever bought had its own room and was the size of a small bear. A bear cub. In order to program it, we had to write our code then type-punch it into paper tape which could be fed into the computer. Some of those programs were pretty long, and one mistake ruined the tape. Luckily I love to type. And play the piano. And do almost anything creative with my hands.

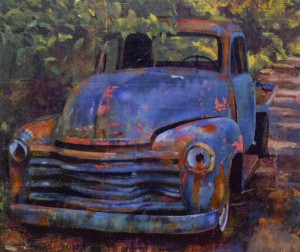

Maybe the reason I love machines better than current computers is because I understand how they work. I mean, I can convert numbers into binary code, but I really have no idea how the computer reads binary or makes sense of it. But give me an old-fashioned internal combustion engine and I can change the spark plugs, the air filter, the oil filter, and the brake fluid. How do I know? Because I used to do it all the time. Nowadays I’m not sure that cars have any of those parts. Fan belts? I don’t know. Everything is electronic.

What fun is that? (aside from power windows, power seats, and butt warmers). I like to know how things work inside. Except people. Too gooey!

Take that, laser level!

Art is full of tools – especially arcane hand tools. Artists get to make stretcher bars, and weld sculptures, and cut glass. We use staple guns and lost-wax casting and linen book-binding thread. I don’t know why everyone isn’t an artist, but it’s okay if you’re not. That just means more art (and more tools) for me.