My interpretation of every dog that lives within six blocks of me.

I’ve only lived in New York since last summer and I love it. I love my apartment building and my neighborhood, Chelsea. I love the subways, the shopping, and of course the art. But I have never seen so many dogs in my life. Not just at one time. I mean cumulatively.

There is a time near evening when the population of 6th Avenue is transformed from its daytime mix of shoppers and students and moms and street vendors into something far different: a horde of just-got-out-of-work-professional-men-still-in-their-business-suits-walking-the-dogs-that-their-wives-and-girlfriends-just-had-to-have.

These are tiny dogs with bouffant hairdos on pink leashes with rhinestones. These are grown men saying things like, “Just wee-wee already, Princess. Daddy is tired.” And, “Come ON, Killer, poo-poo.”

The dogs strain against their leashes no matter which way the men turn, and then suddenly lurch to the side to tangle in the legs of strangers. They sit down, mid-crosswalk, causing cabs to honk ($350 fine, but worth it). They want grass, in a city in which grass lives behind bars.

They do poop eventually, leading to the classic plastic-bag lean-and-scoop maneuver. This is not always performed cleanly and efficiently, to the detriment of innocent passersby.

One presumes that it is love for a woman that causes men to behave like this, since it is certainly not love for a dog. Their expressions of embarrassment and resignation make that clear.

Somewhere nearby, safe at home, is the real pet owner: a woman who says all too often, “Honey, would you take her for a walk, just this once?”

My brother is two years older than I am and has never stopped teasing me. Ever. When I was much younger and thought I would be a writer, he told me that the less successful I was when I was alive, the more successful I would be when I was dead. And that dying young would help. (“Emily Dickinson,” he would say, looking at me pointedly.)

My brother is two years older than I am and has never stopped teasing me. Ever. When I was much younger and thought I would be a writer, he told me that the less successful I was when I was alive, the more successful I would be when I was dead. And that dying young would help. (“Emily Dickinson,” he would say, looking at me pointedly.)

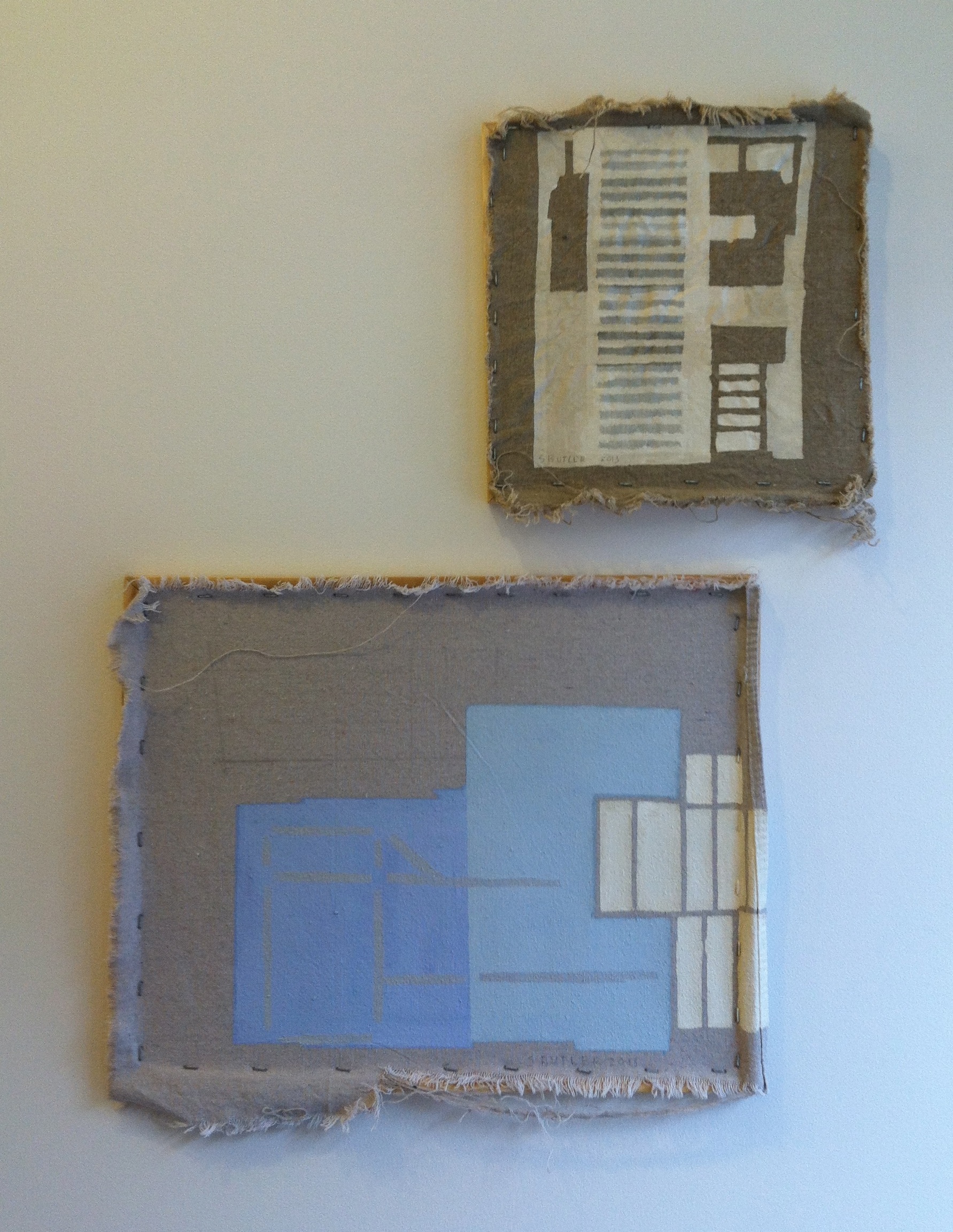

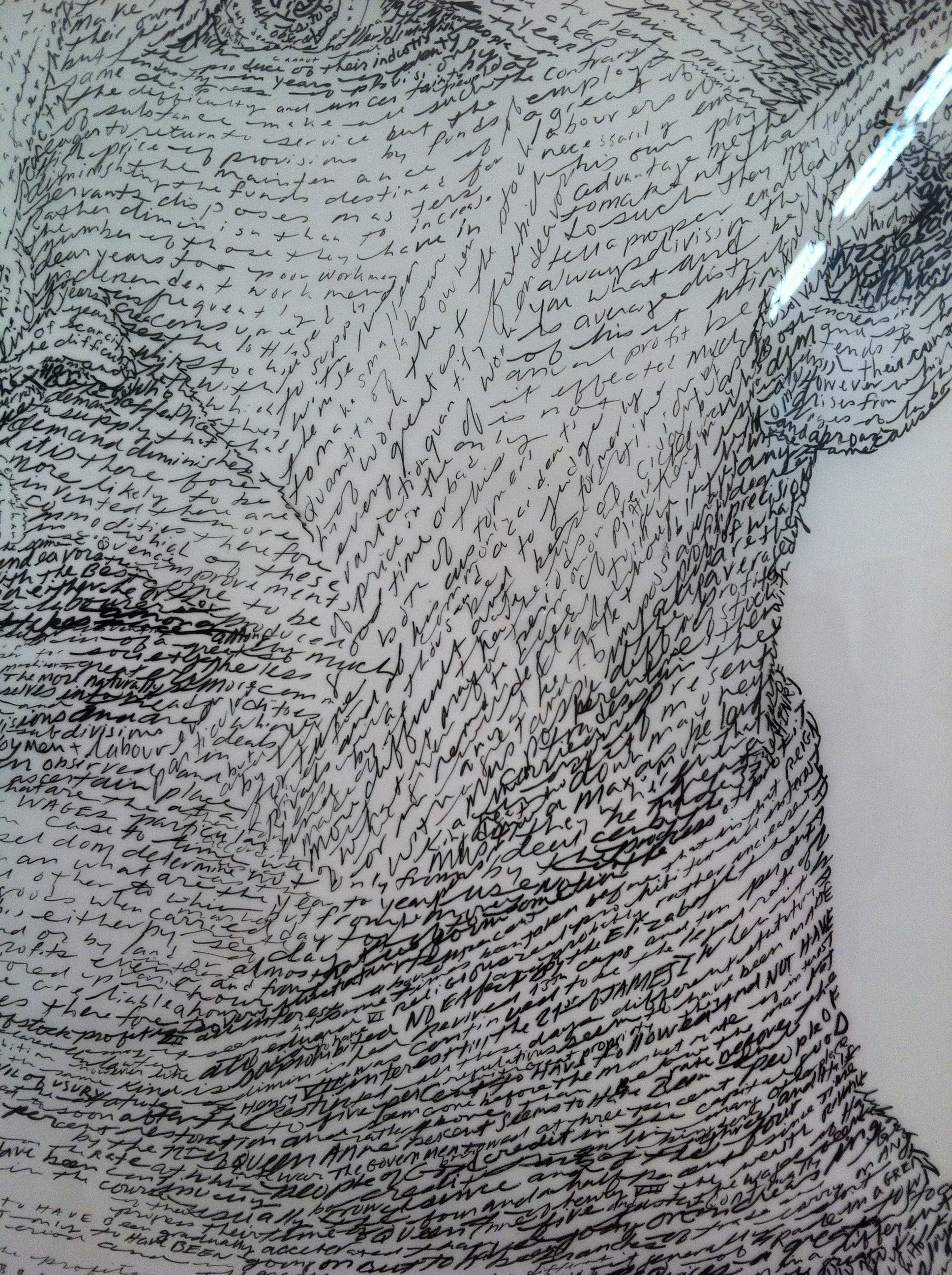

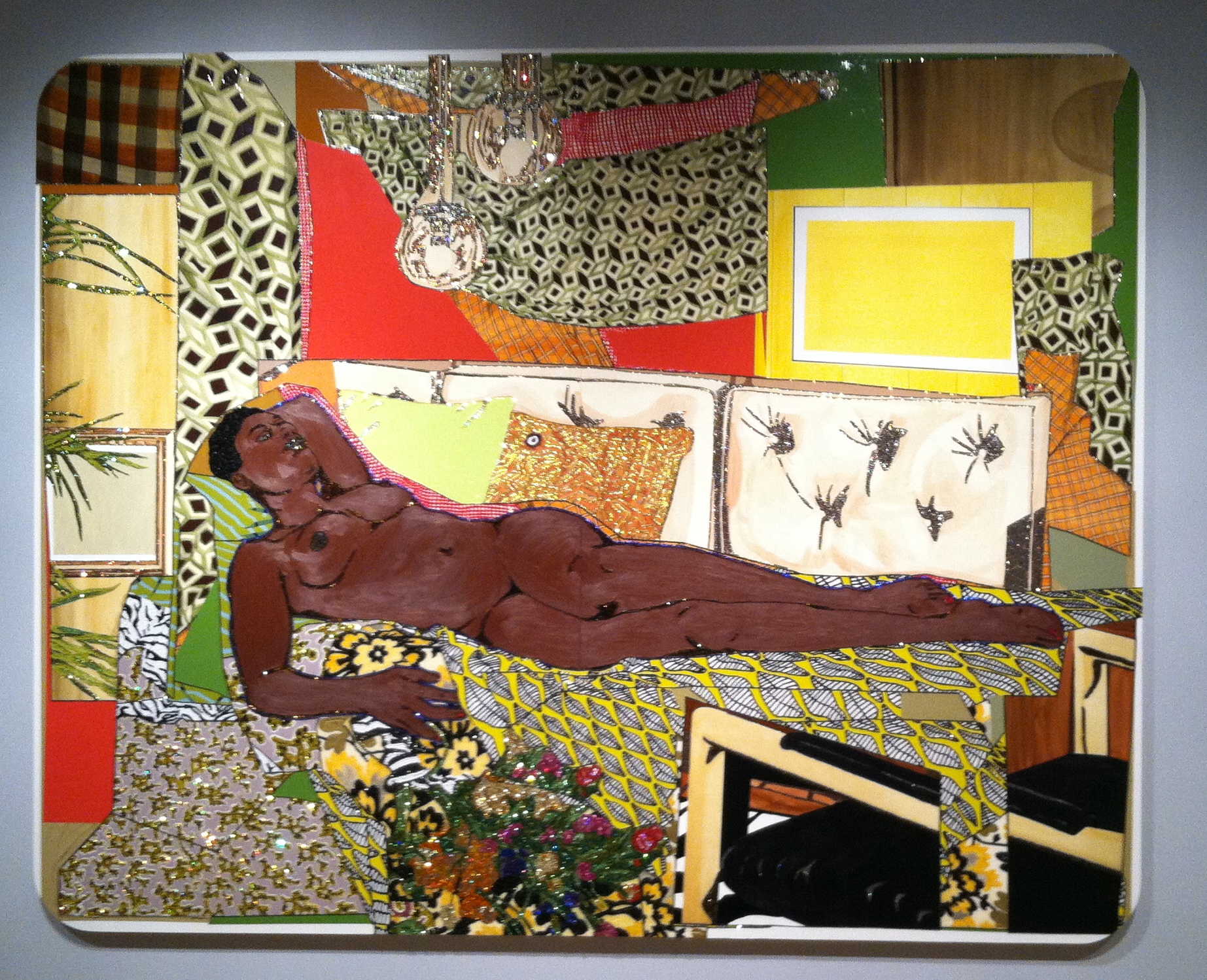

It is rare that an art installation inspires exuberance in viewers, but also rare that an installation so involves viewers in participating and creating the art.

It is rare that an art installation inspires exuberance in viewers, but also rare that an installation so involves viewers in participating and creating the art.